Two-thirds of poll respondents believe there is gerrymandering in Singapore

For years, a particular spot in the North-East of Singapore has befuddled Singaporeans — the area was simultaneously christened Bedok Reservoir, Hougang, and Punggol.

That image posted on Reddit prompted commenters to label it an example of gerrymandering, where electoral boundaries are drawn in a manner favouring the ruling party to prevent opposition candidates from being elected.

Fuelling these accusations is the fact that the People’s Action Party (PAP) has 83 MPs out of 93 contested seats, giving it a supermajority and the ability to push through bills with scant opposition in Parliament.

A debate on electoral boundaries in Parliament opened the door for questions as to whether gerrymandering exists in Singapore.

Minister-in-charge of Public Service Chan Chun Sing asserted in a speech that the electoral boundary review process is “fair and transparent”, and that “elections remain clean and fair”.

But whether the populace believes this is true remains something to be verified.

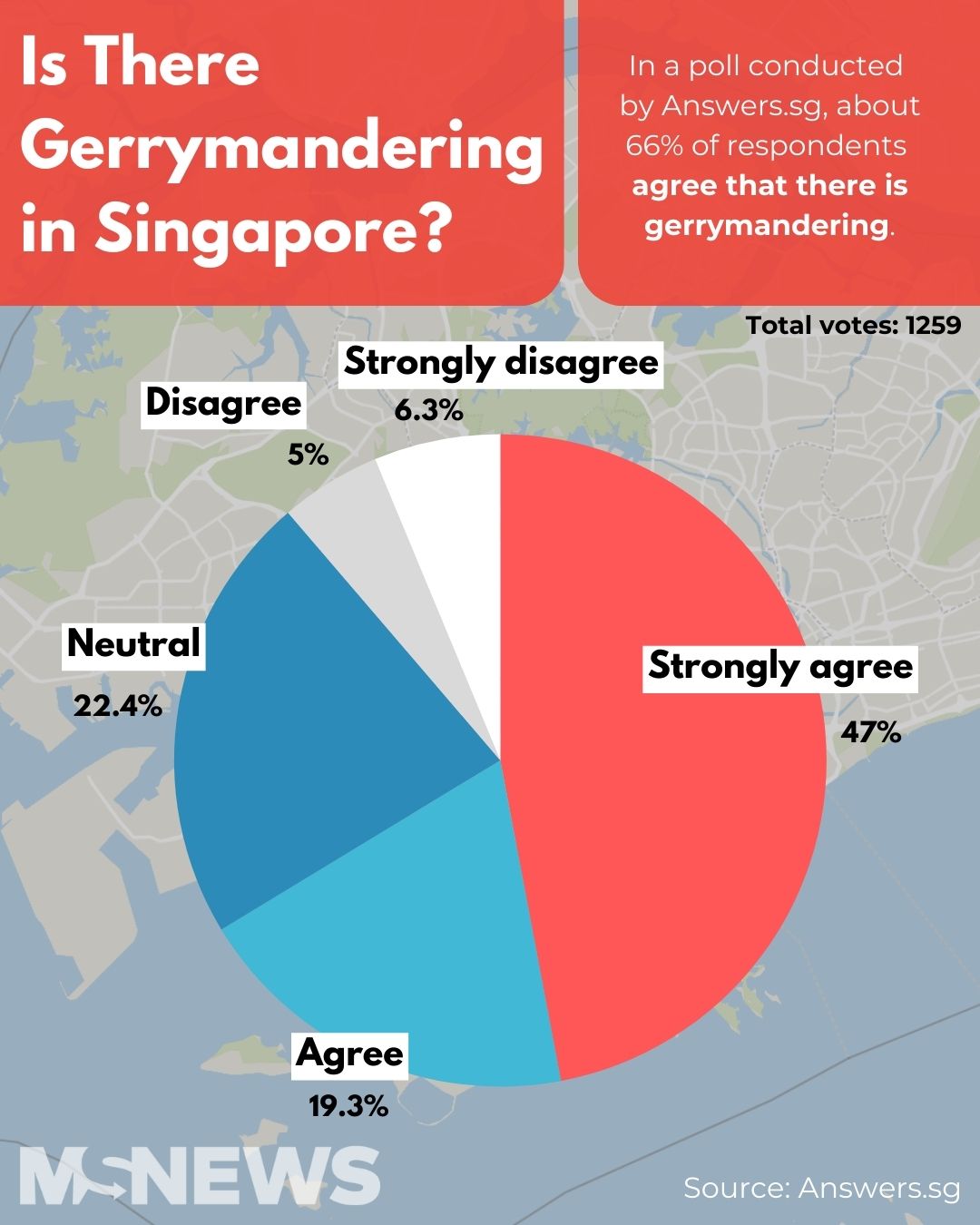

According to a poll on Answers.sg, about two-thirds of 1,259 poll respondents believe that gerrymandering exists in Singapore.

Just 6.3% indicated that they strongly disagree, while 22.4% indicated their neutrality.

It is also worth noting that a third of respondents in a separate poll asking about what gerrymandering is indicated that they were not sure.

MS News spoke to two experts to find out more.

What is gerrymandering?

In order to talk about gerrymandering, we have to provide a definition.

Gerrymandering is the practice of dividing electoral districts, often of a highly irregular shape, to give one political party an unfair advantage by diluting the other political parties’ voting support, associate professor of law at the Singapore Management University (SMU) Eugene Tan told MS News.

Source: Boston Rare Maps

“One cannot answer definitively whether gerrymandering exists in Singapore,” Mr Tan noted. “It is too simplistic and convenient, despite it being a one-party dominant state, to say that it exists in Singapore without robust evidence.”

That said, it is also “hard for the government” to prove that gerrymandering doesn’t exist here, Mr Tan added.

The case of GRCs & SMCs in Singapore

Associate professor of Political Science at McMaster University, Netina Tan, did not hesitate in telling MS News that there is gerrymandering here, based on her past research. Her research focuses on authoritarian resilience, political representation, and digital democracy in Asia and globally, including Singapore.

Ms Tan claims in a paper she co-wrote in 2018 that one of the aims of gerrymandering is to dampen opposition strength in electing its candidates through “stacking”.

“Stacking” in gerrymandering refers to combining areas with different demographic compositions into a single district, which can often create an oddly-shaped boundary.

The intent is to merge a concentration of voters from one party with a larger population of ruling party voters.

This then prevents opposition party voters from electing their preferred candidate.

In the case of Singapore, Ms Tan says this is done via its Group Representative Constituencies (GRC).

Smaller Single Member Constituencies (SMC) are grouped with other constituents with a higher percentage of voters favouring the ruling party.

“Where the opposition showed strength, the boundaries and sizes of the GRCs were changed to submerge that opposition,” she said.

The effects of this can be seen in measurements such as the Gallagher Index, which measures the disproportionality between votes and seats.

It points to Singapore’s electoral outcomes as being one of the “most unequal in the world”, according to an article on The Lowy Institute.

The article noted that the PAP “consistently” had a higher percentage of seats compared to their percentage of votes.

Difficult to show gerrymandering exists, says expert

The Elections Department (ELD) has stated that electoral boundaries are “revised regularly to reflect population growth and shifts”.

It is recommended by the Electoral Boundaries Review Committee (EBRC) which is made up of senior civil servants with the relevant domain knowledge.

“In the absence of evidence that the EBRC does the PM’s [Prime Minister’s] bidding when it comes to deciding on electoral boundaries, it is hard to sustain the assertion that there is gerrymandering,” Mr Tan noted.

He further noted that “one irregularly-shaped electoral district” is not proof of gerrymandering.

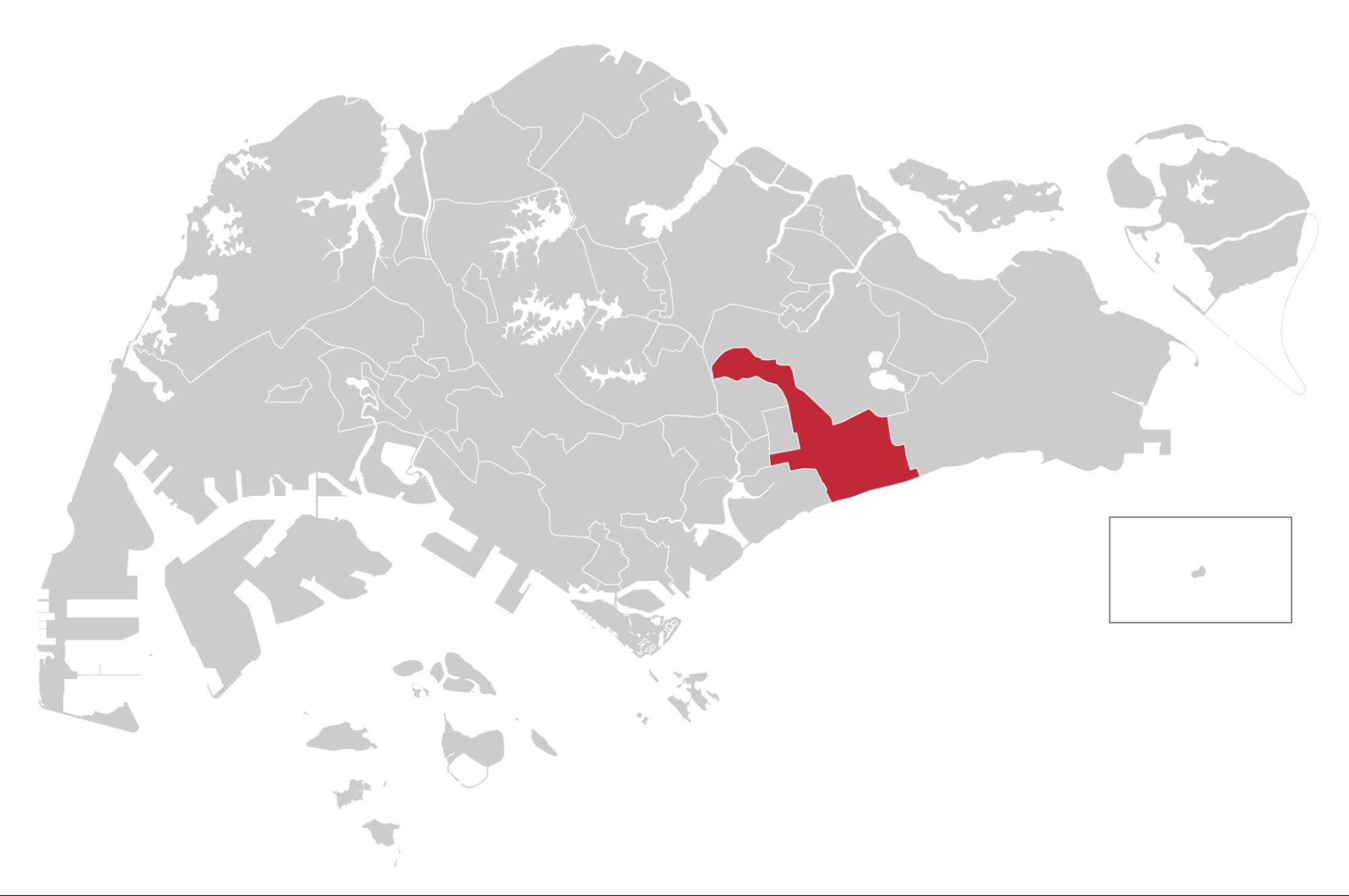

“That there is one irregular-shaped electoral district — and Marine Parade GRC is an oft-cited example — in and of itself, does not prove that gerrymandering exists in Singapore,” said Mr Tan.

Marine Parade GRC as represented by electoral boundaries. Source: Danialrosli on Wikimedia Commons

Conversely, Ms Tan cited past cases where constituencies that were close contests were subsumed or rearranged as part of new GRCs.

“Since 1988, most SMCs with over 40 per cent oppositional voting have disappeared or been submerged into GRCs, such as Braddell Heights, Bukit Batok, Changi, Nee Soon South, Ulu Pandan and Yuhua after 1991,” she said.

“Similarly, several GRCs with more than 40 per cent oppositional support have been dissolved or reshaped. She noted the examples of Moulmein-Kallang after 2011, Cheng San after 1997, Eunos after 1991 and Tiong Bahru after 1988.

“Disproportionate” number of seats relative to voters is evidence of gerrymandering: Expert

Ms Tan said that she has tried to provide evidence of gerrymandering working in the PAP’s favour in her work through factors such as changes in electoral disproportionality, swing ratio of district magnitude, and malapportionment.

The former is when “parties receive shares of legislative seats that are not equal to their shares of votes”.

Swing ratio of district magnitude refers to the relationship between the percentage of votes received by a party and the percentage of seats it wins.

Calculating a swing ratio involves comparing the percentage of votes a party receives in one election to the percentage it received in the previous election, according to Ms Tan’s 2018 paper.

Malapportionment, meanwhile, is when there is a discrepancy between the shares of legislative seats and the shares of the electorate in the constituency. In its last review, the EBRC Committee decided to work on a range of 20,000 to 38,000 electors per MP, based on a swing of 30% variation.

“The plus or minus 30% from ideal used in Singapore provides great room for manipulation,” Ms Tan said.

But according to Ms Tan, in a “fairly apportioned system”, the ratio of the electors for each constituency should be around 1 to the electoral quota, derived from the total electorate divided by the total number of elected seats.

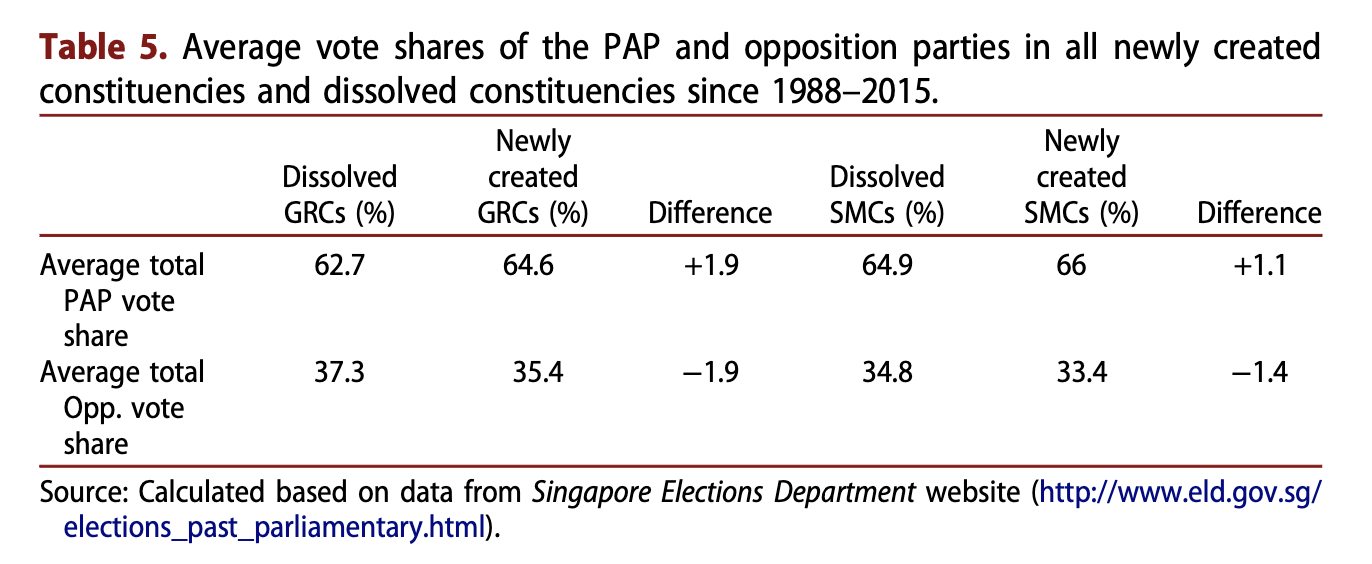

Image courtesy of Netina Tan.

In newly created GRCs or SMCs between 1988 and 2015, the average total vote share for PAP increased by up to 1.9%.

However, Ms Tan said there isn’t clear evidence that this practice of malapportionment has occurred in recent years.

Who appoints the electoral boundary committee if it is to be independent?

An independent electoral commission, according to a Nic Cheeseman and Jorgen Elklit paper, is one that is “institutionally independent from the executive branch of government”.

That (the EBRC) falls under the Prime Minister’s Office is “highly unusual”, according to Ms Tan. “Most countries create independent commissions as part of the global movement to depoliticise the redistricting process.”

Examples include Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and India. The committee should be “independent from politics” and have a strong legal standing, as well as be able to make decisions that go against the interests of the ruling party, Cheeseman and Elklit said.

But Mr Tan said the EBRC has to be appointed by someone, and that could end up being the highest seat of government due to the nature of who runs elections committees in Singapore.

“So long as you have the Prime Minister (PM) or some other political figure who does so, then the allegations of the process being politicised will persist.”

“This is also the case if you have a non-politician making the appointments — who appoints this person then? The reality in a parliamentary system of government is that the head of government wields this power, either directly or indirectly,” Mr Tan noted.

Regardless, he said that one way to ensure the EBRC’s independence is for it to be legislated in the Parliamentary Elections Act with safeguards to protect their appointments and independence.

Redrawn boundaries are a disadvantage to opposition parties, but not due to gerrymandering, says expert

Mr Tan also had a counterpoint to the claims that electoral boundaries being redrawn equates to gerrymandering, claiming this is “often about political parties externalising their lack of competitiveness” rather than any tampering on the part of the establishment.

“Political parties have the agency to make themselves competitive,” he said, further noting: “Saying that there is gerrymandering is a criticism of the Singaporean voter — that we tolerate gerrymandering for the past 60 years.”

The PAP stands to lose less from electoral boundaries being redrawn, simply because it contests every GRC and SMC.

If, however, an opposition party can do the same, they would face fewer problems with redrawn boundaries.

While Mr Tan acknowledged that the current slate of opposition parties stands to be impacted significantly by redrawn boundaries, he asserted that it is “something such parties have to be aware of”, rather than pointing the blame at the EBRC.

The Workers’ Party (WP), for example, mitigates the impact of redrawn electoral boundaries by “generally contesting in electoral districts that are contiguous to each other”, he noted.

Electoral boundaries being redrawn isn’t sufficient evidence

As Mr Tan notes, the belief that gerrymandering is practised here is not enough to show that it exists, especially if unsubstantiated with evidence.

One example is Braddell Heights in Marine Parade GRC. “It… may make for a good sound bite but fails miserably in making the case that there is gerrymandering of the sort that they are fingering,” he said.

“…when Braddell Heights was absorbed into Marine Parade GRC, it was not a SMC that the PAP was in grave danger of losing,” Mr Tan further noted.

Opposition-held wards have generally not been touched by the EBRC despite there being a lower voter population, he said. One example he gave was Potong Pasir SMC, which was held by Chiam See Tong between 1984 and 2011.

Source: Alchetron

Hougang SMC, too, has not been touched, while the WP won Sengkang GRC after Punggol East SMC was merged into the GRC in 2020.

“There are countless permutations as to how electoral boundaries can be redrawn. It is not a science,” Mr Tan explained. “Furthermore, when one electoral district’s boundaries are redrawn, there is a knock-effect on other electoral districts.”

EBRC could give explanations for redrawn boundaries

However, he feels the EBRC could go into more detail as to why certain GRCs and SMCs are oddly shaped. Ms Tan also argued that the EBRC has not given explanations for recent SMC and GRC changes, especially since 2011.

This was the case, she said, for the dissolution of Joo Chiat SMC, a hotly contested seat by WP in 2011.

Mr Tan suggested legislating that a certain minimum period — between three to six months — must have elapsed first between the public release of the EBRC report and the calling of a general election.

He also suggested that the membership of the EBRC be legislated in the Parliamentary Elections Act with safeguards to protect their appointments and independence.

“Who controls the redistricting process is also critical if we want to understand the effects of electoral rules,” Ms Tan noted. “Without an independent election commission, opposition checks in Parliament, or an appeal process, unilateral boundary changes can have partisan effects.”

Belief that gerrymandering exists can be detrimental to voters

Whether people think that gerrymandering exists is important because this belief can lead voters to “feel they are being largely disenfranchised”, because their votes no longer matter, Mr Tan said.

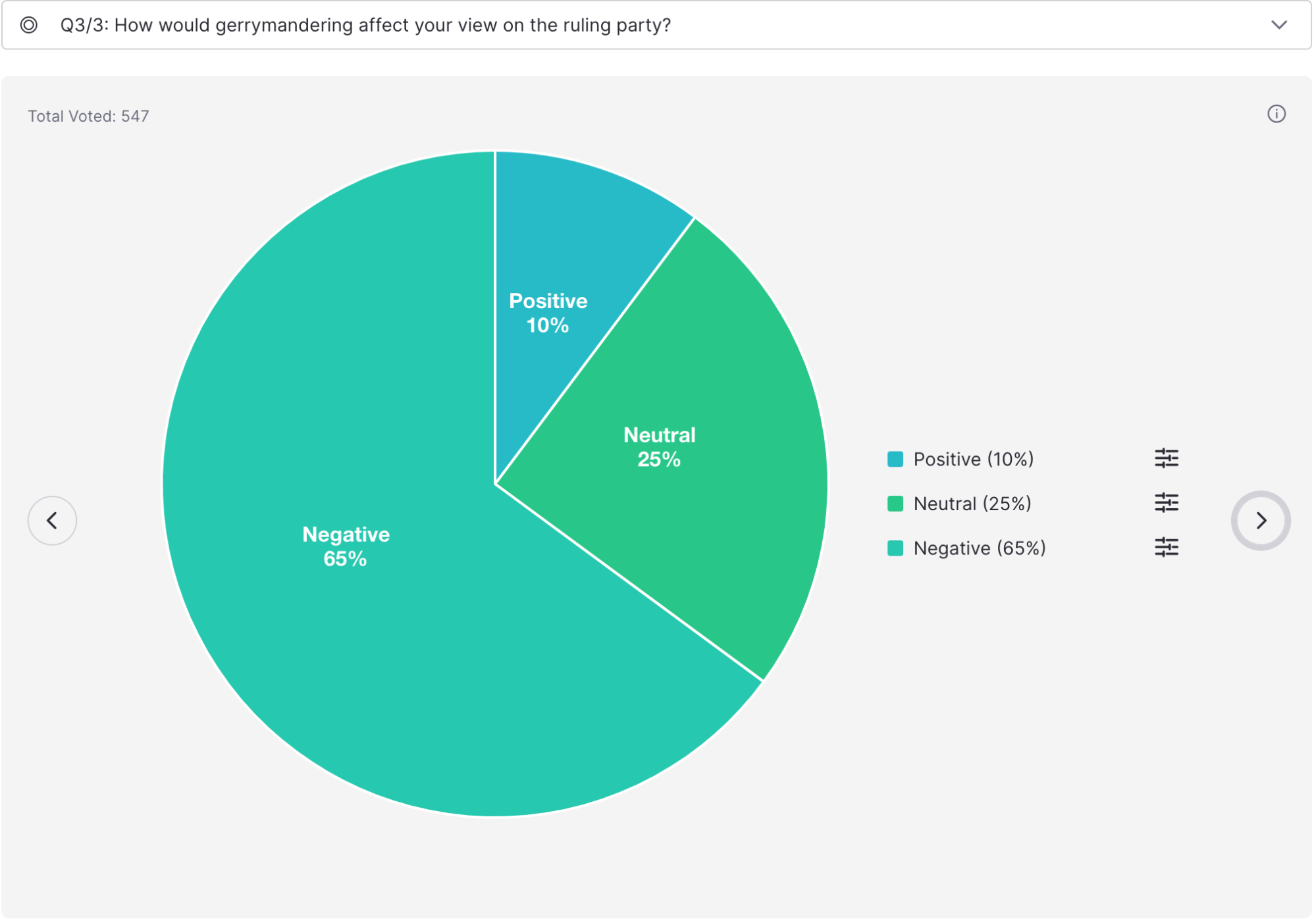

The poll results indicate that gerrymandering would result in a negative view of the ruling party among more than two-thirds of respondents.

One participant in the poll, Mr Ang, said he would like for elections to be fair.

“Otherwise, it doesn’t matter who I vote for, right? I might as well spoil my vote if it doesn’t matter,” the 33-year-old, who declined to give his full name or occupation, said.

Ms Tan added that gerrymandering, if it exists, “dilutes the voting power of certain groups”.

It would also reduce electoral competitiveness between parties and candidates as well as undermine electoral trust and disenfranchise voters, leading to a less representative government.

It is unclear if the current process for electoral boundary drawing will change, given the Government has explicitly called it “fair and transparent”.

In light of that, it is on all candidates to be aware of potential electoral boundary changes, and ultimately, look at how best to get elected.

As Mr Chan pointed out in his speech in Parliament:

Singaporeans are discerning voters, and so I urge all candidates to fight an election on substance. Earn the trust of the electorate with concrete actions. Focus on how to serve the voters and gain their trust, wherever you choose to stand, rather than thinking about excuses for not being able to do so.

Have news you must share? Get in touch with us via email at news@mustsharenews.com.

Featured image adapted from Reddit.