The Pulau Senang prison experiment in the 1960s

This piece is part of MS Explains, a segment where we provide clarity to common or key topics, making them easier to digest.

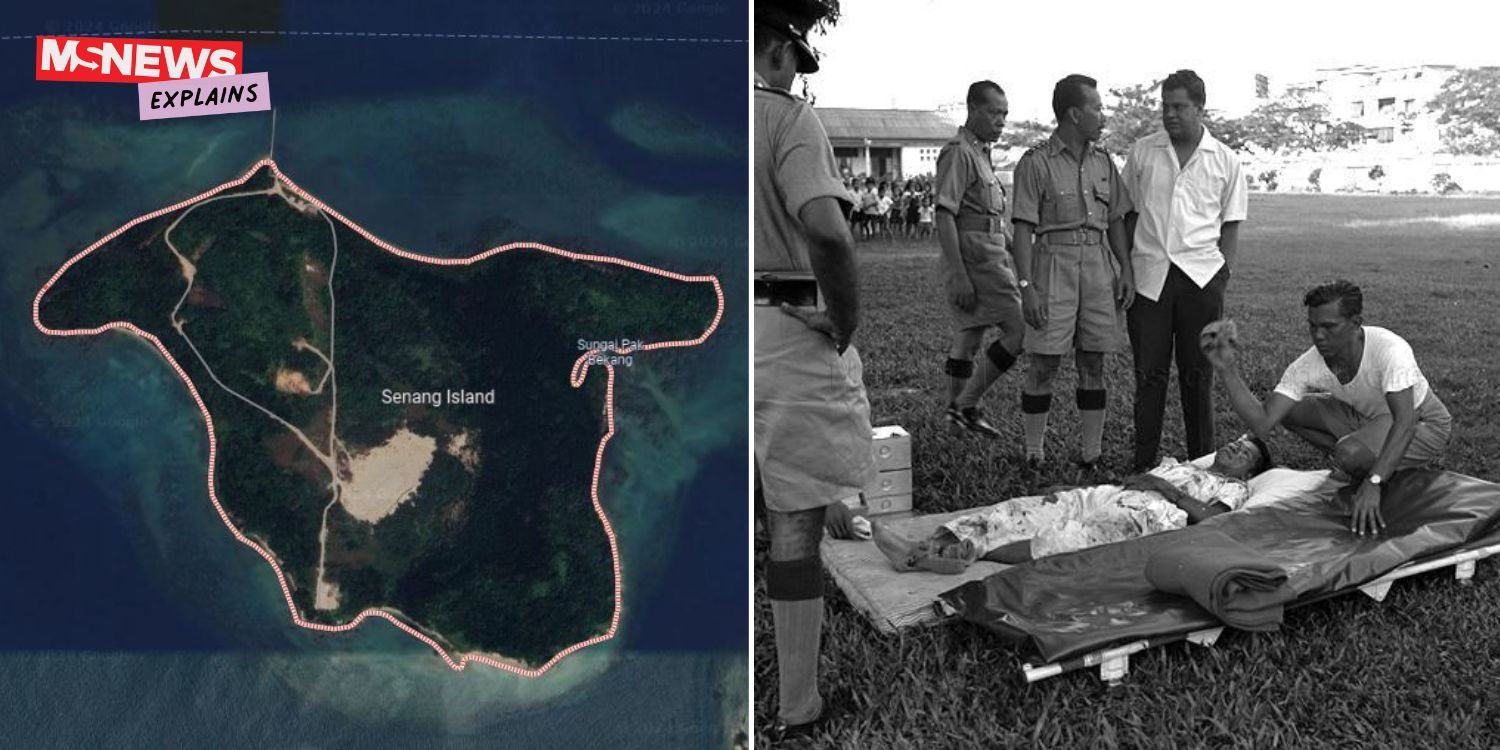

Thirteen kilometres off the southern coast of mainland Singapore lies a 202-acre island called Pulau Senang.

In Malay, ‘senang’ means ease, although the island’s history as Singapore’s prison experiment was far from that.

Billed as a rehabilitation location for hardened secret society members in a period when they were running rampant, Pulau Senang was meant to prove that humanity could prevail over criminality.

But a mere three years after the experiment started in 1960, the prisoners rebelled and the island, quite literally, went up in flames.

This is the story of how an island filled with promise turned into grounds for bloodshed.

Pulau Senang was the brainchild of a former prisoner

Pulau Senang was initially envisioned as an open-air prison where prisoners would be treated humanely and rehabilitated through building the island’s infrastructure.

The late Devan Nair, once a political prisoner of the British in the 1950s, had been appalled at the way prisoners were treated and sought to reform the system.

Amid overcrowding due to a crackdown on Singapore’s rampant secret society, Pulau Senang was picked as the site of the new experiment for its “shark-infested waters” and strong currents, according to Kevin Tan, an adjunct professor at NUS’ law faculty, on Channel NewsAsia (CNA).

The conditions were thought to have made it tough for prisoners to escape, he added.

Source: Google Maps

The man tasked to run the experiment was Superintendent Daniel Dutton, who had experience in the Prison Service and had served in the military.

He was an idealist — someone who believed that everyone was deserving of rehabilitation.

Through hard work, he was quoted as saying, anyone could be “saved”, and then brought back to society.

And so it went, as Dutton arrived on the island in May 1960 with around 50 prisoners, hoping to transform prisons as we knew them.

Growing unrest despite initial acclaim

With Dutton spearheading the development, the detainees built various amenities such as dormitories, offices, a hospital, and recreation areas, according to the National Library Board (NLB).

By 1962, they managed to build a dining hall, kitchen and bakery, too. The number of prisoners more than doubled as well.

Source: National Archives of Singapore

Pulau Senang came to be known as the Island of Hope, reported ST in 1965.

Despite the glowing acclaim by local politicians including Lee Kuan Yew, as well as the United Nations, rumours of growing unrest over Dutton’s “slave-like” work conditions persisted.

Source: National Archives of Singapore

Neivelle Tan, who according to CNA had been detained on Pulau Senang for a short time, heard from others that Dutton would make the prisoners work relentlessly.

Though Dutton would work hard alongside the secret society members, he’d reportedly shout and curse at them to keep working. Inmates were also supposedly asked to work at night.

If someone refused, they’d be punished and threatened to be sent back to prisons on the mainland.

Per CNA, a rehabilitation officer named Chia Teck Whee, nicknamed “Ah Chia”, was also a target of ire, according to former detainee Tan Sar Bee.

Chia would reportedly send detainees to solitary confinement and was called a “bully”.

Other reports indicated that there was occasional unrest — on 22 April 1963, ST reported that there was a “pitched battle” between detainees and wardens involving changkols, a tool used to dig up soil.

The offenders were routed by a reserve unit called in from Singapore, and sent to Outram Prison.

Anyone who misbehaved would be disciplined by the wardens or sent to another prison. Dutton was confident of being able to control the prisoners and did not even arm wardens with weapons.

But behind the scenes, the hardened criminals on the island were preparing to strike back.

Retaliation

Around a week before the fateful riot on 6 July 1963, Dutton sent 13 detainees to Changi Prison for refusing to work on a 400-foot jetty on a Saturday afternoon — a rest day.

In the following few days, a group of conspirators, which included detainee Tan Kheng Ann, drew up a list of people to kill, including Dutton. They would go on to start the riot.

Another long-time detainee, Chong Sek Ling, testified in court that he had overheard and subsequently revealed the plan for rebellion to Dutton. He had done so as he had high regard for Dutton’s integrity.

However, it seemed that the warning fell on deaf ears.

Tan said to CNA that Dutton was “absolutely confident” that the majority of the detainees were with him, which was a delusion.

Detainees strike

At around 1pm on 12 July 1963, more than 70 rioters made their move. Armed with weapons such as changkols, parangs (a type of knife), and even bottles, they marched up to the wardens and attacked.

They even went for other detainees who refused to join in.

Meanwhile, several detainees set fire to the main store and the radio room, where Dutton had fled.

They poured gasoline into the enclosed room and lit it up, forcing Dutton out — where four detainees were waiting for him with axes, reported ST.

He met his end there, hacked to death in a brutal fashion. Dutton had never carried a firearm on Pulau Senang, believing that his fists were enough to keep the detainees in line.

Source: National Archives of Singapore

To the end, he held on to his hope that he could rehabilitate these men.

By the time reinforcements came from the mainland at 1.55pm, Dutton was dead. He’d been mutilated and burnt.

His death was brutal and unforgiving — the detainees appeared to have a particular grudge against him, though other prison officers weren’t spared.

One man celebrated Dutton’s slaying by hanging his blood-soaked shirt on a mast.

Three others, Tan Kok Hian, a fellow prison officer, along with two other wardens, had also died as a result of the riot.

Several others were critically injured, including rehabilitation officer J. W. Tailford as well as a prison warden.

Source: National Archives of Singapore

18 men sentenced to death by hanging

With the riot and Dutton’s death, the experiment was deemed a failure and shut in 1964.

59 detainees were put on trial and charged with murder and rioting.

Source: National Archives of Singapore

By the end of the 64-day trial, 18 men were found guilty of murder and given the death sentence.

Another 29 were jailed for rioting or rioting with deadly weapons, and the rest were acquitted.

Source: National Archives of Singapore

The men were eventually hung on 29 October 1965.

Pulau Senang experiment stops after riot

The penal colony on Pulau Senang began with the aim of rehabilitating hardcore gangsters through manual labour in a prison without bars. It ended in disaster, culminating in a bloody riot.

Though the experiment was deemed a failure and the island never saw use as a prison again, at least one person believed it was a success: Dutton’s brother, Michael.

“You still came out, to me, as the winner because you proved that the system would work,” he said.

Today, Pulau Senang, along with other nearby islands, is part of the Southern Islands Live Firing Range, where military exercises are conducted.

Also read: An SAF Boys’ School once trained teens for army career, students had free meals & received allowance

An SAF Boys’ School once trained teens for army career, students had free meals & received allowance

Have news you must share? Get in touch with us via email at news@mustsharenews.com.

Featured image adapted from Google Maps and National Archives of Singapore.