What happened to Ramadan bazaars in Singapore?

This month, a bazaar vendor and a TikTok reviewer got into a spat so bad that lawyers have gotten involved.

Here’s the gist of the story: The reviewer had made “brutal”, less than ideal remarks about the stall’s offerings, and the vendor got really mad.

This ongoing fiasco has me scratching my head. Since when did Ramadan bazaars become a part of the social media circus?

The bazaars of my childhood were frequented by families shopping for Hari Raya clothes while soaking in the wholesome, festive vibes.

Now, we see booth after booth of IG-worthy food — and while it’s encouraging to have more entrepreneurs in the community, the bazaars have lost a bit of their magic.

Ramadan bazaars have lost favour with the community

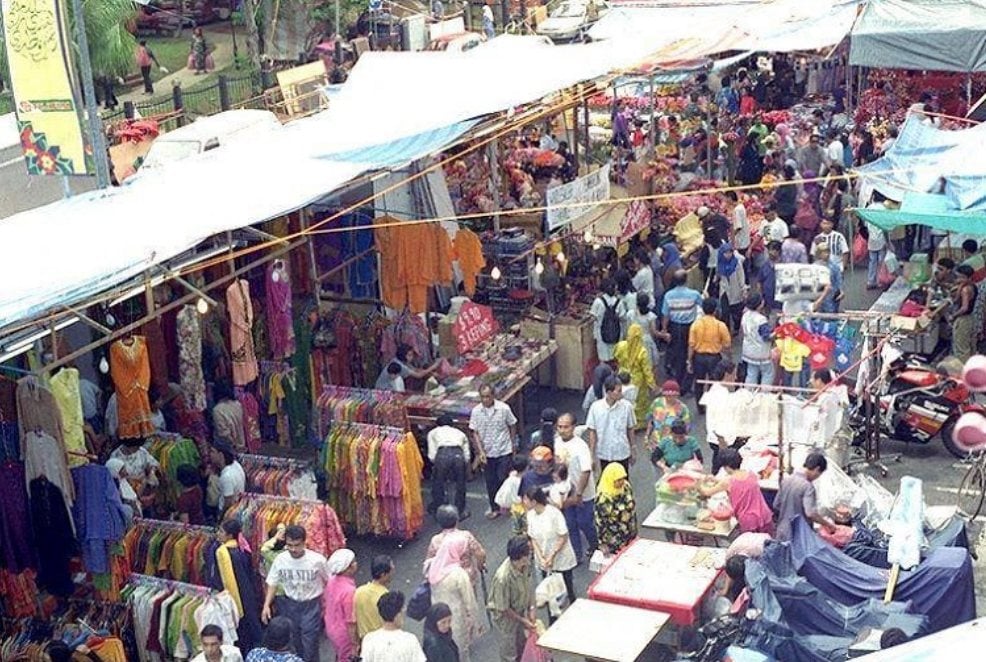

The smell of hearty, fried food, a maze of stores selling rugs, baju raya, and even curtains, as far as the eye can see.

Growing up in the 2000s, these were my memories of the Geylang bazaar — the only bazaar I remember frequenting. It was a pasar malam on steroids and it was glorious.

What’s left of this sprawling bazaar now is a (relatively) small square at Geylang Market and Food Centre.

My recent visit to the Geylang bazaar lasted a grand total of 15 minutes, most of which was spent waiting for my parents to finish queuing for food.

I went home craving bubble tea and feeling severely underwhelmed by my fleeting experience there.

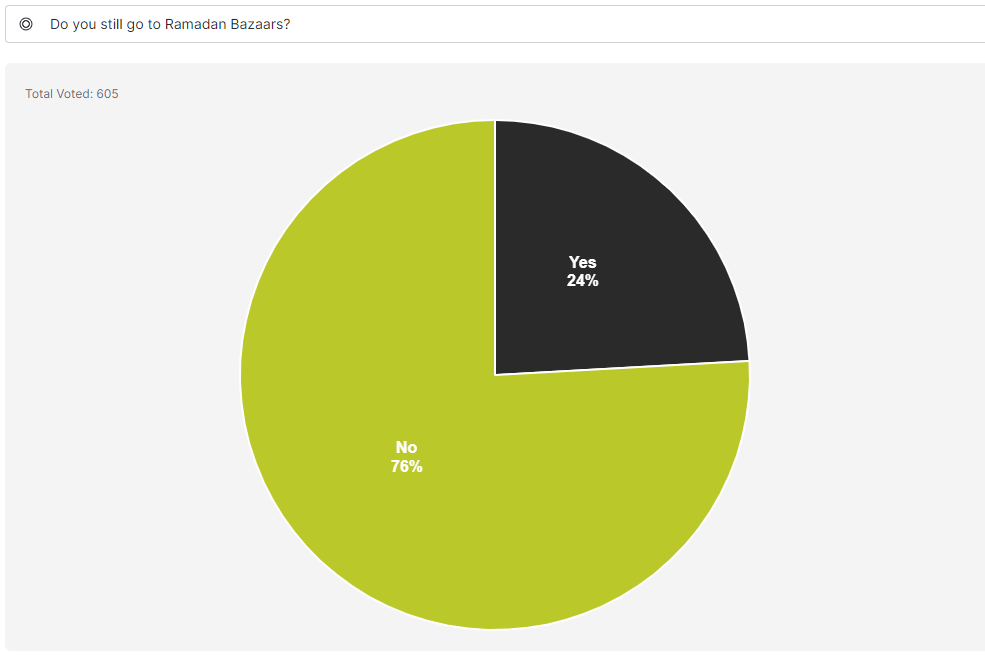

Am I the problem? As it turns out, others are feeling the same disillusionment. In a poll with more than 600 respondents, 76% said that they no longer visit Ramadan bazaars.

Source: Answers.sg

Others on social media noted that they haven’t stepped foot in a bazaar in more than a decade.

Noriko Farahsyazwani, a restaurant assistant manager, shared that the bazaars now are “too modernised” and not as “traditional” as they used to be.

Because of this, her mother, who runs a food catering business, decided against being a vendor at this year’s bazaar.

“We used to open back then, long ago, in 2003. We had queues because people appreciate nasi padang in bazaars,” recounted the 28-year-old F&B professional. “Nowadays I doubt so.”

Ramadan bazaars now a haven of IG-worthy food

Perhaps Noriko’s comment isn’t too off the mark. Just take a look at the offerings at this year’s Geylang Serai Ramadan Bazaar.

There are fries packed in a giant cigarette box (cute), churros that have “localised” flavours, and even a stall selling straight-up Philly cheesesteak.

The offerings are not the bazaar’s or the vendors’ fault. In a world where virality could make or break your business, it becomes less about the food and more about the idea of it.

Perhaps it makes sense then that most of the stalls being featured online are those with unique concepts.

Unfortunately for the consumer, unique food also means a higher price point.

“My pani puri (an Indian street food) was S$12 for 10 balls,” said Ain Zainal, a 30-year-old senior creative at an F&B company.

She had purchased the dish at this year’s Geylang bazaar, where she generally found the food options and space to be lacking.

“I felt like I was in a normal weekend pasar malam as compared to a festive bazaar.”

Among “novelty food items that cost a bomb”, Ain also observed few stalls selling satay, ikan bakar, or even kueh.

Go across the Causeway and you’ll easily find these traditional Malay street food offerings at Malaysia’s festive bazaars.

In Singapore, trendy food — which now happens to be food from outside the Malay culture — dominates amid soaring rental costs for vendors.

High rentals put pressure on vendors to make money

This year, the rents for the Geylang Serai Ramadan bazaar are going for as high as S$15,000, reported the Straits Times (ST).

Base rentals for the 2023 bazaar ranged between S$2,000 and S$19,000. Additionally, vendors who wanted to sell Ramly burgers had to pay a S$4,000 premium.

With such high costs, businesses face the pressure of having to innovate and come up with offerings that are unique — not just delicious.

It’s no wonder that mom-and-pop shops selling “basic” pasar malam fares have been pushed out by newer, sexier food concepts.

The Ramadan bazaar has become a victim of the social media age. Vendors need to be trendy to survive.

What were Ramadan bazaars like in the past?

In the good ol’ days, the one or two bazaars were gathering points for the Malay community because they were a one-stop shop for everything Raya-related.

My earliest memory of the bazaar was buying a matching set of baju kurung (traditional Malay attire) with my family.

I spent hours browsing rows upon rows of stalls. But now, I spend minutes scrolling through online shops.

For 53-year-old housewife Aminah Rahman, her memories of the Geylang Serai bazaar in 1980s are colourful ones.

Source: Ross Bridal on Facebook

“Just walking through the bazaar without purchasing anything was pure enjoyment and happiness,” she said, noting the bazaar’s lively atmosphere back then.

“We even had people reciting pantun (Malay poems) on the loudspeaker while selling bunga kembang malam (flower arrangements for the home).”

Aminah cheekily recalled instances when the sellers disturbed the young girls passing by, but it was all in good fun.

Those who visited the Geylang bazaar from 1998 to about 2019 may remember Mohamad Arshad Mohd Yaqoob, more popularly known as Raja Bunga — an icon of the bazaar.

He would sit atop his chair, selling his flowers using a megaphone or a microphone.

Source: Berita Harian Singapura on Facebook

Mr Mohamad Arshad passed away in 2020, taking with him the unique talent of bringing life to the bazaar.

Too many bazaars, all selling similar things

Apart from flowers, the bazaar vendors of the 1980s sold Hari Raya necessities such as baju raya, house decorations, songkok (traditional headgear), and sandals.

As it turns out, there wasn’t much food at all, only “basic Raya kueh” such as pineapple tarts and makmur (a pastry filled with a sweet peanut filling), noted Aminah.

Somewhere along the way, Ramadan bazaars became known for their food and are no longer the place for general shopping.

It certainly doesn’t help that there are so many bazaars now that we need lists of all of them to even keep up.

There are at least 10 Ramadan bazaars and pasar malams this year — including the Geylang Serai and Kampong Gelam bazaars.

And everywhere, I expect the offerings to be the same. Ridiculously massive 3-litre drinks (because apparently, that’s trending right now), S$10 fries, and other Western snacks of the sort.

What’s the point of even heading down?

Bring back the bazaars of my childhood, I’m sick of “trendy” food

My feelings about the Ramadan bazaar might just be a me problem, as someone who gets random bouts of nostalgia and longing for how things were.

But in a life where the only constant is change, there’s comfort in things that stand steadfast against time.

I’m not saying that all bazaars have to offer nostalgic, local food — that in itself would be repetitive, boring, and also, unprofitable.

But would it hurt to have one bazaar modelled after the ones of the past?

Trends come and go, but that doesn’t mean those that did disappear forever. Look at Y2K fashion — low-rise jeans and baggy cargo pants from that era are back again after years of high-waisted bottoms.

Perhaps in the name of trends, it could be in businesses’ interests to appeal to nostalgia, to bring back what’s now hard to find.

Have news you must share? Get in touch with us via email at news@mustsharenews.com.

Featured image adapted from Muhammad Rusydi Bin Rasip on Facebook and Gemilang Kampong Glam for illustration purposes only.

Drop us your email so you won't miss the latest news.