Rehab Expert Shares Experiences In Counselling Radicalised Individuals

While the 9/11 attack happened far away in the United States, its effects reverberated globally. The resulting fear of another attack led to counter-terrorism efforts that continue today.

Al-Qaeda, who claimed responsibility for 9/11, would spawn offshoots focusing on different regions, including one many of us will be familiar with—Jemaah Islamiah (JI).

As we approach 8 Dec 2021, 20 years since 15 people connected with the terrorist group were arrested, MS News talked to Dr Mohamed bin Ali, an Assistant Professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS).

He shared the work he does with the Religious Rehabilitation Group (RRG), which counsels not only JI detainees and Restriction Order (RO) supervisees but also family members and self-radicalised extremists in recent years.

Called to rehabilitate radicalised individuals in 2003

Dr Mohamed, 48, shared with MS News that his initial goal was to become a religious teacher.

However, upon his return from his undergraduate studies at Al-Azhar University in Cairo, he received news from his father, a religious leader in the community, that would change his entire life’s trajectory.

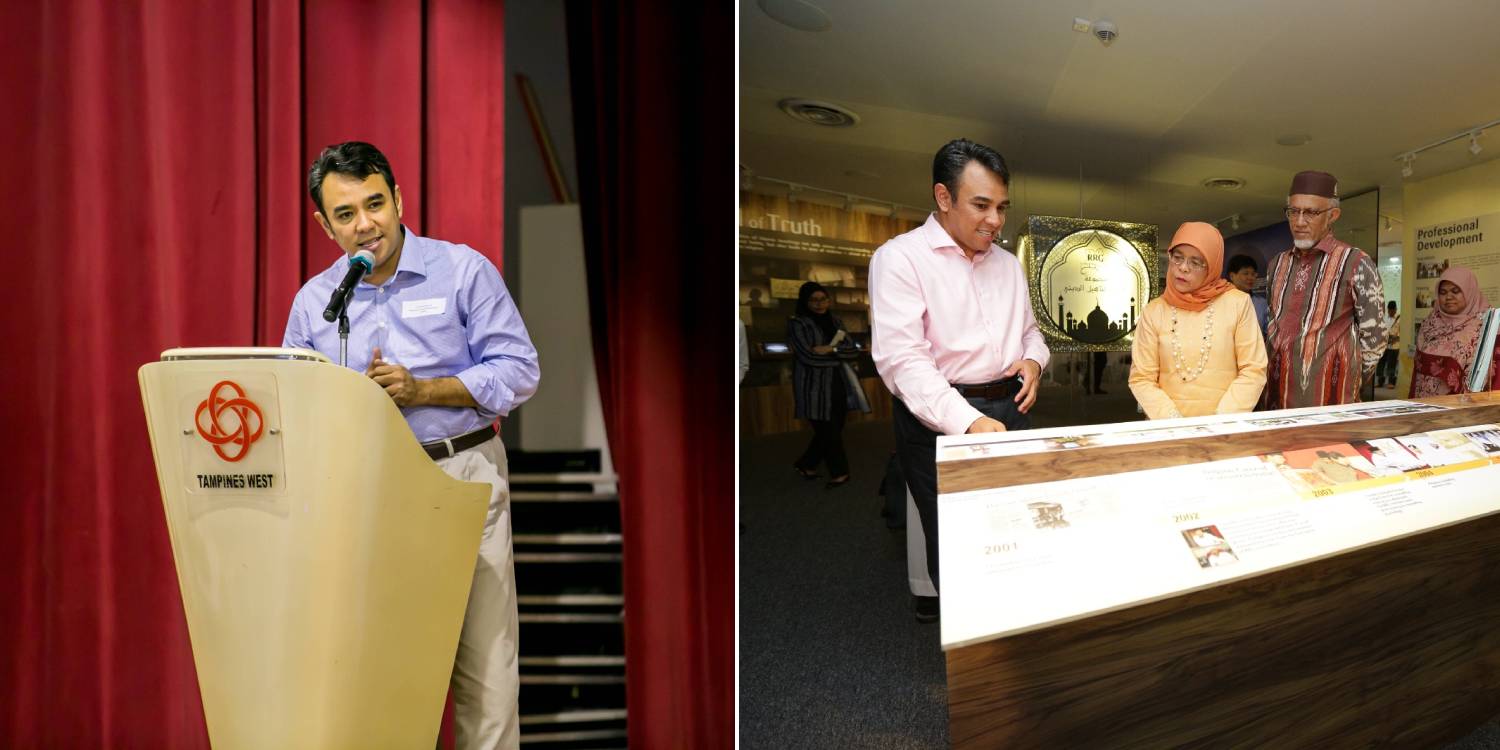

Dr Mohamed speaking at an inter-faith dialogue event organised by Tampines West IRCC. Image courtesy of Dr Mohamed Ali

In early 2002, the Internal Security Department (ISD) approached and consulted several well-respected senior religious leaders.

Among them were Ustaz Ali Haji Mohamed and Ustaz Hasbi Hassan, who are currently co-chairmen of RRG. They concluded that the JI members had been misguided by its leaders and had a wrong religious interpretation.

Thus, the RRG, which Ustaz Ali Haji Mohamed and Ustaz Hasbi Hassan co-founded, was established to counsel these misled detainees and supervisees, and it continues its work until today.

To deepen his knowledge and understanding of terrorism, Dr Mohamed promptly left his job as a mosque manager to enrol in the International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research at NTU in 2004.

Since then, Dr Mohamed has poured countless hours into studying terrorism, culminating in an NTU scholarship to do his PhD in Arab and Islamic Studies, which he completed in 2013.

The formation of JI

JI would become the catalyst that led Dr Mohamed to his life’s work.

JI was founded by Indonesians Abu Bakar Bashir and Abdullah Sungkar in the 80s. The group’s political goal was to create an Islamic system of governance in Southeast Asia.

This included Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Southern Philippines, and Thailand.

There were plans by JI members to target various landmarks in Singapore, including the water pipelines and Yishun MRT station.

The radicalisation process was done through religious classes held in residential homes. Individuals would visit under the assumption that these were typical religious classes, only to be taught an extremist form of Islam—one that is intolerant of non-Muslims and secularism.

Its goal is to fight in the name of Islam to establish an Islamic state. This, of course, is a distortion of Islamic teachings.

Authorities got wind of JI’s terrorist activities and arrested 15 people under the Internal Security Act (ISA) in Dec 2001 and another 21 in Aug 2002.

While this effectively dismantled the Singapore cell, the threat of terrorism regionally remained high—notably with the Bali bombings in 2002.

Gaining the trust of radicalised individuals

Dr Mohamed shared that the Internal Security Department (ISD) adopts a comprehensive and holistic rehabilitation programme consisting of three components: psychological rehabilitation, religious rehabilitation, and social rehabilitation.

The RRG handles the religious rehabilitation portion in particular.

The first step to rehab: begin to know him. Understand his thinking, background… to build a connection and rapport.

This might take a couple of sessions—each session lasts between 1 and 2 hours.

Dr Mohamed noted that the JI detainees initially viewed RRG with distrust and suspicion as they believed they were “stooges of the government'”.

Regardless, the counsellors pushed on with their convictions to guide the detainees back on the right path.

If the detainees did not trust us, then what’s the point of talking to them?

Some of the people Dr Mohamed counselled experience other issues within their lives that led them to become radicalised.

They may also possess anti-government sentiments. Extremism provides an alternative to the establishment for such individuals.

However, RRG have also counselled radicalized individuals who are highly educated and with good employment and family background too.

The point is that radicalisation can affect anyone regardless of their background, especially through the Internet or social media.

Correcting religious understanding of radicalised individuals

At the same time, the counsellors also try to identify the issues that need to be addressed regarding religious understanding.

For example, the idea that jihad is “fighting (for) the cause of Islam” and having negative conceptions of Islam, such as how Muslims should lead their lives in a secular society like Singapore.

Once these issues are identified, the rehab will move on to the third step: correcting their misunderstandings or misperceptions.

We need to help them appreciate living as a Singaporean — in a multi-racial society. And we need to help them appreciate living as a Muslim in a secular environment… and within a pluralistic society.

In assessing whether a detainee is ready for release, ISD considers whether the individual has let go of their radical beliefs and has demonstrated the willingness to re-integrate into society, among other factors.

The evolution of terrorism over the years

One significant aspect that RRG has noticed changed over the years is the profiles of the detainees.

The initial JI detainees were generally aged between 30-50 and were radicalised physically in clandestine religious classes.

But in 2007, a self-radicalised individual was found. The proliferation of the Internet and social media has meant a global threat from terrorist organisations like the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS), who use social media to spread their extremist ideologies.

As a result, the age profiles of the radicalised have drastically changed in recent times, with many aged between 19-30.

Far-right extremism is also a growing concern on social media, with ISD arresting a 16-year-old Singaporean who planned to target 2 mosques in Singapore. He is the youngest ever detainee.

As terrorism and its ideologies have evolved, so has the RRG to combat these threats.

The RRG’s role in the community

Dr Mohamed points out that the issue to tackle is not with any religion but with extremism as a whole.

Therefore, it is an issue that all of Singapore’s leaders, not just leaders in the Muslim community, have to solve.

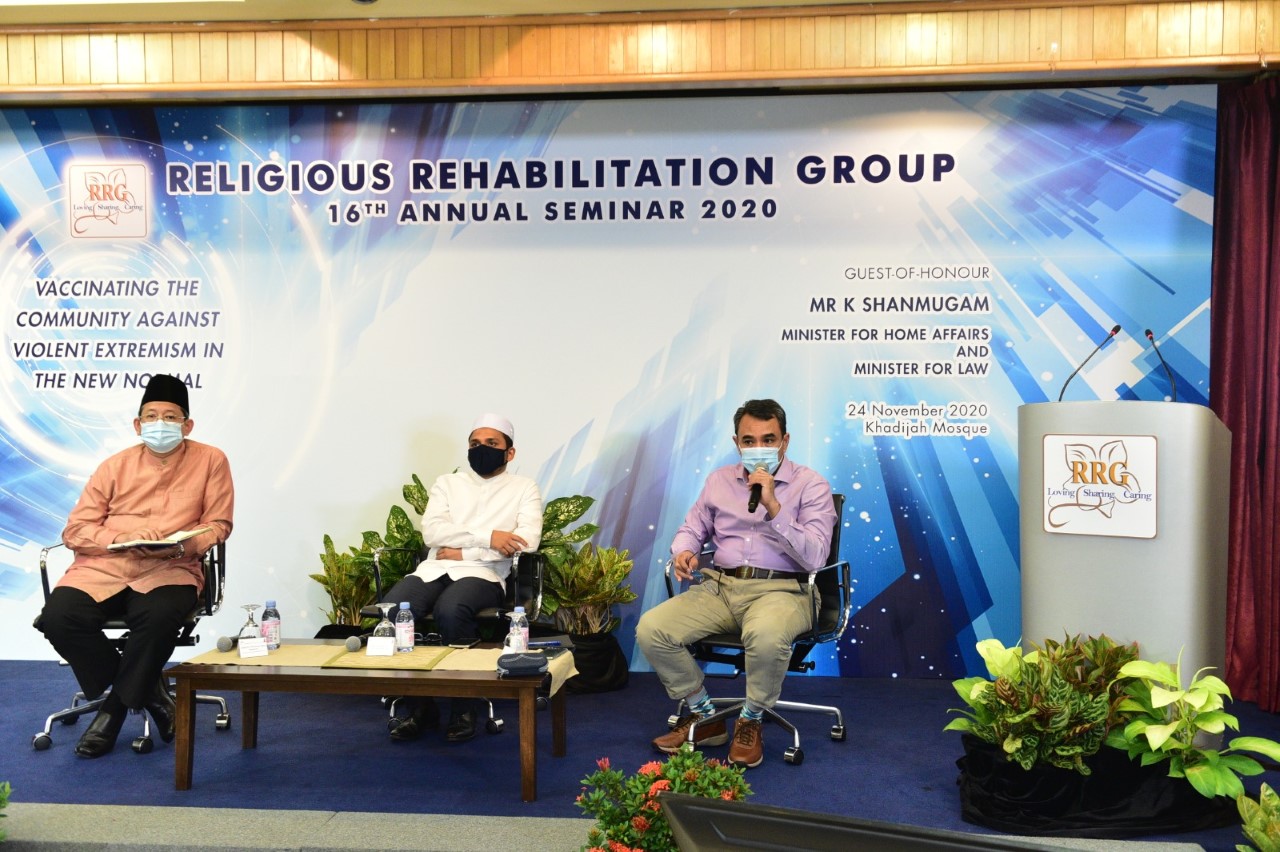

Dr Mohamed Ali speaking at a panel discussion at the RRG 16th Annual Retreat 2020. Image courtesy of Dr Mohamed Ali

It also takes a collaborative approach between the government and RRG to function — but on one condition: that RRG remains entirely voluntary.

This, Dr Mohamed felt, was the best way to gain the community’s trust. “Otherwise, it’s just a job,” he said.

RRG is grateful for the trust and support that ISD gave to RRG in counselling and rehabilitating radicalised individuals.

Although the RRG is mainly engaged in rehabilitating detainees, the work that Dr Mohamed and other religious leaders do also extends to the community, such as outreach programmes at schools.

Dr Mohamed Ali briefing President Halimah Yaacob and husband during a visit to the RRG Resource and Counselling Centre. Image courtesy of Dr Mohamed bin Ali

The families of detainees, many of whom depend on them as the sole breadwinner, are also given financial, psychological, and social support through the Aftercare Group (ACG) initiative.

Detainees are provided with assistance to look for jobs and opportunities upon their release to reintegrate well into society.

In many cases, this is successful enough that “many of the people in public…they forget [the detainees’] past”, Dr Mohamed said, but this takes effort. “Efforts to show that we care.”

To find out more about the RRG and its work, including behind the scenes, you can check out their website.

Rehabilitating radicalised individuals is Dr Mohamed’s life work

RRG members do not always publicise their work due to the confidentiality and sensitive nature of their job. As a result, the public – or even their loved ones – do not know the intensity and arduous process of counselling the ISA detainees.

Through our talk with Dr Mohamed, we sensed that rehabilitation, although not his primary job, constitutes his life’s purpose.

When asked how long he’d continue his counselling work, Dr Mohamed wryly replied that he’d probably be doing this for the rest of his life.

As long as terrorism exists, counter-terrorism efforts will be needed—so his RRG work may never be complete. A task that requires a conviction and sincerity that goes beyond any paid job.

Since the JI arrests in 2001 were the main catalyst for where he is today, he quipped that without that event, he’d probably have gone on to be a religious teacher.

This speaks volumes about how one does not have to take up arms to defend Singapore.

What Dr Mohamed shares in common with a soldier, is their love for our country and their desire to protect our way of life.

This article is part of MS News’ commemorative project to reflect on how our lives have changed since the JI arrests in 2001.

Featured image courtesy of Dr Mohamed Ali.